Helping to create a single integrated market across Africa is in the west’s interests

A lack of jobs and opportunity at home is driving the flow of migrants from the continent

The writer is secretary-general of the African Continental Free Trade Area

Misinformation may have sparked the UK’s anti-immigration riots, but anxieties

over illegal immigration are hardly confined to British shores. Pressured by voters,

governments across Europe are scrambling for solutions. Conversely, African

governments are concerned about the exodus of the educated and entrepreneurial

— the dreaded brain drain that stymies development. Yet many of those who leave

would, given the choice, prefer to stay at home, anchored in bonds of family,

culture and community. Economic circumstances conspire against this modest wish.

Recognising the reality, Britain’s new Labour government has pledged £84mn for

projects in Africa and the Middle East to address factors driving people to flee.

While the funding is welcome, it will fail to bring the economic change Africa

requires to stem the root cause of migration: a lack of jobs and opportunity.

True transformation hinges on the rollout of the African Continental Free Trade

Area (AfCFTA) — a landmark agreement that binds 54 nations and about 1.47bn

people into the world’s largest free trade area. Though rising, Africa trades less

with itself than any other continent — changing this will be critical for African

prosperity.

What the continent does send to the rest of the world locks it in lopsided trading

relationships. A legacy of the colonial era, exports from Africa are dominated by

primary goods such as coffee beans, cocoa and raw minerals, leaving it vulnerable

to the vicissitudes of global commodity markets. Outside the continent, refining,

processing and manufacturing add value to these raw materials. Finished goods

are then imported back into Africa, thwarting the continent’s ambitions to become

an economic powerhouse.

However, when African nations engage in trade among themselves, processed and

manufactured goods form more than 42 per cent of their commerce. The AfCFTA

will dismantle tariffs on 97 per cent of total tradeable products within the bloc,

drastically cutting the costs of trade to drive volume. Rather than exporting jobs

abroad, Africa stands to unlock labour-intensive industrialisation throughout the

continent.

World Bank projections illuminate the AfCFTA blueprint. The initiative is slated to

lift 50mn people out of extreme poverty, increase continental incomes and boost

intra-African trade. Meanwhile, investment on the continent could surge as much

as 159 per cent. A vast integrated market casts a wider net for global capital,

mitigating the risk of investing in individual nations and enabling economies of

scale.

To realise this ambitious project, international allies are essential. In 2021, the UK

became the first nation outside Africa to sign a memorandum of understanding to

boost trade with the AfCFTA, committing funds and providing trade policy

expertise to support its implementation. It is vital that the new Labour

government continues this work. Not only does it open markets and investment

opportunities for UK businesses on the continent, it also offers a co-ordinated

approach to comprehensively address irregular migration.

More allies are needed. While the AfCFTA holds the greatest promise for African

prosperity, significant hurdles remain in its implementation. Technical challenges

in streamlining regulatory regimes and digitalising customs procedures persist.

Substantial investment is needed to produce made-in-Africa products that will

spur decent jobs on the continent.

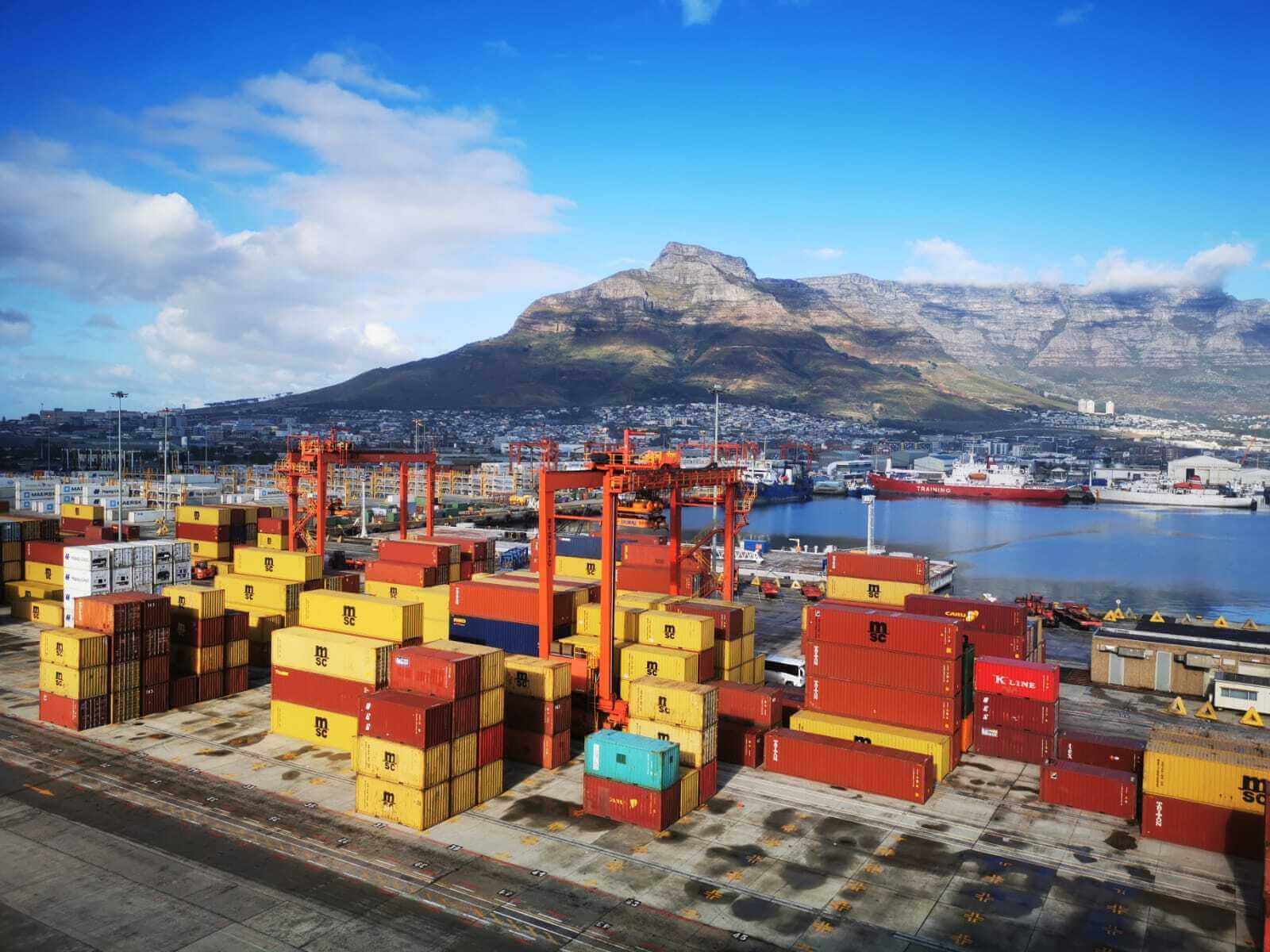

Above all, the continent’s fragmented transport and logistics networks need

investment. Freight lines primarily transport goods from the interior to coastal

ports for export, neglecting regional needs. Greater international collaboration is

required. The partnership between British International Investment, the UK’s

development finance institution, with Emirati logistics company DP World to

support the modernisation and expansion of ports and inland logistics across

Africa is a step in the right direction. But the continent is still facing an

infrastructure funding gap of about $100bn annually.

Yet despite formidable challenges, the AfCFTA is making headway. Launched in

2018, its rollout was delayed by the pandemic and the ripple effects of the war in

Ukraine. Nevertheless, in October 2022 the first shipments under the AfCFTA

framework took place: Kenya and Rwanda exported batteries, tea and coffee to

Ghana. These countries, together with six others, formed a pilot aimed at testing

the framework and identifying necessary adjustments. This year, it expanded to

include a further 39 nations including South Africa and Nigeria, which exported

fridges, bags, ceramics, textiles, cables, smart cards, clinkers, black soap, native

starch and shea butter.

Deep and wide integration will take time. But without structural economic

transformation in Africa, the supply of migrants to the west will rise. There is only

a long-term solution to this challenge. Better to begin the work now.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2024. All rights reserved.